|

0004. The End of Economic Man: The Origins of Totalitarianism (1939) by Peter Ferdinand Drucker

...ประเทศเยอรมัน

ระหว่างปี ค.ศ. 1933-1945 อดอล์ฟ ฮิตเลอร์ (Adolf Hitler) เป็นผู้นำ (ฟือเร่อ) ของประเทศเยอรมนี และ เป็นผู้นำของพรรคกรรมกรสังคมนิยมแห่งเยอรมนี หรือพรรคนาซี(nazi)

... อดอล์ฟ ฮิตเลอร์ (ขวา) และ มุสโสลินี (ซ้าย)

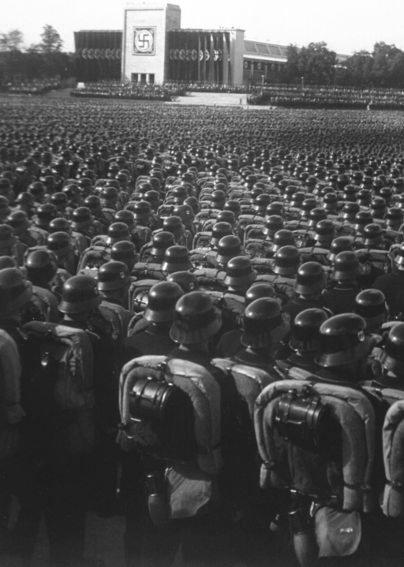

...กองทัพเยอรมันในปี 1935 การชุมนุมที่นูเรมเบริ์ก

.... ที่ประเทศ อิตาลี

เบนีโต อามิลกาเร อานเดรอา มุสโสลีนี

(Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini)

เรียกชื่อโดยทั่วไปว่า "อิลดูเช" (Il Duce) แปลว่า "ท่านผู้นำ" เป็นจอมเผด็จการและนายกรัฐมนตรีของประเทศอิตาลี (พ.ศ. 2465พ.ศ. 2486)

หรือ October 31, 1922 July 25, 1943

31 ตุลาคม พ.ศ. 2465 เบนิโต มุสโสลินี (Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini) ก้าวขึ้นเป็นนายกรัฐมนตรีของอิตาลี ขณะอายุ 39 ปี ถือว่าเป็นนายกฯ ที่อายุน้อยที่สุดของอิตาลี เรียกชื่อโดยทั่วไปว่า "อิล ดูเช" (Il Duce) แปลว่า "ท่านผู้นำ" มุสโสลินีเป็นนายกรัฐมนตรีจอมเผด็จการในช่วง พ.ศ. 2465 2486 ก่อนหน้านั้นในปี 2462 มุสโสลินีได้ก่อตั้งพรรค "ฟาซิดี คอมแบตติเมนโต" หรือพรรค "ฟาสซิสท์" (Fascist) พ.ศ. 2468 เขาได้สถาปนาตนเองเป็นเผด็จการเต็มรูป บังคับให้ยกเลิกระบบรัฐสภา แทนด้วย "รัฐบรรษัท" (Corporate State) รวบอำนาจอย่างเป็นทางการ จัดตั้งรัฐวาติกัน ยึดอบิสซีเนียละอัลบาเนียเป็นเมืองขึ้น พร้อมกับการประกาศเข้าร่วมเป็นฝ่ายอักษะกับอดอฟ ฮิตเลอร์แห่งประเทศเยอรมนี ในที่สุดมุสโสลินีถูกจับได้โดยฝ่ายต่อต้านชาวอิตาเลียนเมื่อปี 2488 ถูกยิงแล้วนำศพไปแขวนประจานที่เมืองโคโมและเมืองมิลาน

ที่ประเทศญี่ปุ่น

นายพลฮิเดกิ โตโจ

...1941 นายพลฮิเดกิ โตโจ นายทหารคนสำคัญก็ได้เป็นนายกรัฐมนตรี และนับตั้งแต่นั้นมาประเทศญี่ปุ่น ก็มีรูปแบบการบริหาร แบบฟาสซิสต์เหมือนในยุโรป ทางด้านเยอรมนี ...

...ประเทศสยาม หรือ ประเทศไทย

นายกรัฐมนตรีไทย คนที่ 3

ดำรงตำแหน่ง

สมัยที่ 1: 16 ธันวาคม พ.ศ. 2481 1 สิงหาคม พ.ศ. 2487 (ลาออก)

สมัยที่ 2: 8 เมษายน พ.ศ. 2491 16 กันยายน พ.ศ. 2500 (รัฐประหาร)

จอมพล แปลก พิบูลสงคราม หรือที่เรียกกันทั่วไปว่า "จอมพล ป." เป็น นายกรัฐมนตรี ที่มีเวลาดำรงตำแหน่ง รวมกันมากที่สุดของไทย คือ 14 ปี 11 เดือน 18 วัน มีนโยบายที่สำคัญคือ การมุ่งมั่นพัฒนาประเทศไทย ให้มีความเจริญรุ่งเรืองทัดเทียมนานาอารยะประเทศ มีการปลุกระดมให้คนไทยรู้สึกรักชาติ โดยออกประกาศสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี ว่าด้วย "รัฐนิยม" หลายอย่าง ซึ่งบางอย่างได้ประกาศเป็นกฎหมายในภายหลัง หลายอย่างกลายเป็นวัฒนธรรมของชาิติ เช่น การรำวง ก๋วยเตี๋ยวผัดไทย เป็นผู้เปลี่ยนชื่อ "ประเทศสยาม" เป็น "ประเทศไทย" และเป็นผู้เปลี่ยน "เพลงชาติไทย" มาเป็นเพลงที่ใช้กันอยู่ในปัจจุบัน

คำขวัญที่รู้จักกันดีของนายกรัฐมนตรีผู้นี้คือ "เชื่อผู้นำชาติพ้นภัย" และ "ไทยอยู่คู่ฟ้า"

และ

Peter F. Drucker

....Peter F. Drucker ได้เขียนหนังสือเล่มแรกในปี ค.ศ. 1939 ชื่อ The End of Economic Man: The Origins of Totalitarianism (1939)

The End of Economic Man: The Origins of Totalitarianism (1939)

The End of Economic Man

The Origins of Totalitarianism

By: Peter F Drucker

ISBN: 9781560006213

Format: Paperback, 276pp

Publisher: Transaction Publishers

Price: $24.95

ถ้าจะให้แปลเป็นไทย ผมให้ชื่อว่า...

อวสานของเศรษฐกรหนุ่ม : จุดเริ่มต้นของลัทธิเผด็จการ

โดย ปีเตอร์ เอฟ ดรักเกอร์

Totalitarianism

: ลัทธิรวบรวมอำนาจ

total

: รวมทั้งหมด, ยอด

tatally

: เด็ดขาด, เบ็ดเสร็จ,เลยทีเดียว

| Create Date : 16 มีนาคม 2551 |

|

15 comments |

| Last Update : 18 มีนาคม 2551 18:03:33 น. |

| Counter : 5870 Pageviews. |

|

|

|

By Mr. D. S. Stadler (London, UK) - See all my reviews

I've been a fan of Druckers for many years but did not get around to reading his first book until very recently.

This is not the usual Drucker fare, though fellow readers will recognize his reach and style. In this book Peter Drucker attempts nothing less than to explain what Totalitarianism (particularly Facism and Nazism) are about. And I think he largely succeeds.

But the subject is 60 years ago, so why buy it now? Because the book also explains much of what is going on today. The alienation many of us feel, the deadening effects of globalization on our economic and inner lives is echoed in this book. Why do Palestinians blow themselves up and Austrians and Frenchmen vote for Haider and Le Pen?

Because capitalism fails to satisfy identity and equality needs. Not just income equality but status equality. Many of Drucker's later books attempt to solve some of capitalism's legitimacy and equality deficiencies, but globalism has rolled back much of the progress which has been made.